There has only been one woman to own the car that has won the Indianapolis 500 – Maude Yagle. Maude was victorious as car owner less than a decade after women were granted the right to vote and yet, forty-two years before women were allowed into the garage and pitlane at Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

If you Google Maude, you’ll likely be disappointed, as there are just a few facts commonly known about Maude: she bought a car in 1928 which she entered into the Indianapolis 500 using the name M.A. Yagle to avoid detection (which promptly failed), and she won the Indianapolis 500 in 1929 with Ray Keech, entered the race again in 1930, failed to qualify in 1931 and disappeared from the motorsport world, her obituary not even acknowledging her accomplishments.

And while all of that is mostly true, there is more to Maude’s story.

Maude Yagle was born Maude Fegley on March 19, 1883, to Frank Fegley and Flora Renn. Maude was born and grew up in Shamokin, Pennsylvania – a small coal-mining town.

As such, her father – like his father, was a coal miner. And like many who worked in the coal mines, it was a dangerous job and the pay was low. By the time Maude was 17, she and her older sister Jennie were both working in a stocking factory while her 13-year-old brother, Raymond worked as a day laborer to help make ends meet for the family of nine.

By 1910, Maude had moved from her family home to Philadelphia, likely in search of opportunities greater than what she might have in Shamokin. The 1910 Census has Maude listed as a lodger in a home on Columbia Avenue and she worked as a loomer in a mill.

In March 1911, she married Edward C Yagle. Two years younger than she, Maude’s husband was a successful businessman who dabbled in real estate as well as construction. Edward wasn’t the only businessman in the household, Maude also dabbled in real estate – her name can be found in newspapers’ real estate transaction sections.

Like many wealthy people of this time, the Yagles both developed an affinity for motorsports. Edward took the step from fan to sponsor in 1926, sponsoring a local phenomenon named Ray Keech. It was this relationship that formed between Ray Keech and the Yagles that would later put Maude onto the path of car ownership.

In 1928, Ray Keech wanted to be the fastest man in the world.

He had his sights set on the land speed record so he traveled down to Daytona Beach in February. However, he returned home with minor burns from a burst water hose and no record. Ray was undeterred and immediately began making plans to return to Daytona.

Returning in April with a rebuilt car, Ray was triumphant, setting the land speed record of 207.552 mph.

Through this, Ray befriended another racer hell-bent on being the fastest man in the world — Frank Lockhart. Frank Lockhart won the Indianapolis 500 two years prior in 1926 and was the polesitter the year after his win.

Frank Lockhart didn’t just have the makings of a great driver, he used his engineering abilities to build custom cars. Frank Lockhart was on a path that was destined for greatness.

Just days after Ray triumphed at Daytona Beach, tragedy struck. During an attempt to break Ray’s land speed record, a tire blew on Frank Lockhart’s car and he lost control of the car and was fatally injured.

Frank Lockhart was only 25.

Grieving the loss of his friend, Ray Keech traveled to Indianapolis with Frank’s manager. On this trip, Ray publicly expressed a desire to race in one of the surviving cars that Lockhart had designed for the upcoming Indianapolis 500.

It is unknown how Maude came to own Frank Lockhart’s car — whether Ray Keech had contacted a past sponsor and it was the sponsor’s wife who jumped at the opportunity, or if she heard about the opportunity to own the car elsewhere. But no matter how it happened, ultimately, Frank Lockhart’s car entered into the 1928 Indianapolis 500 with Ray Keech behind the wheel and Maude as the car’s owner.

And maybe it was because the media was distracted by the story of Ray Keech driving Frank Lockhart’s car, Maude’s ownership went unnoticed by newspapers, despite his solid tenth qualifying spot and his even better fourth place finishing position.

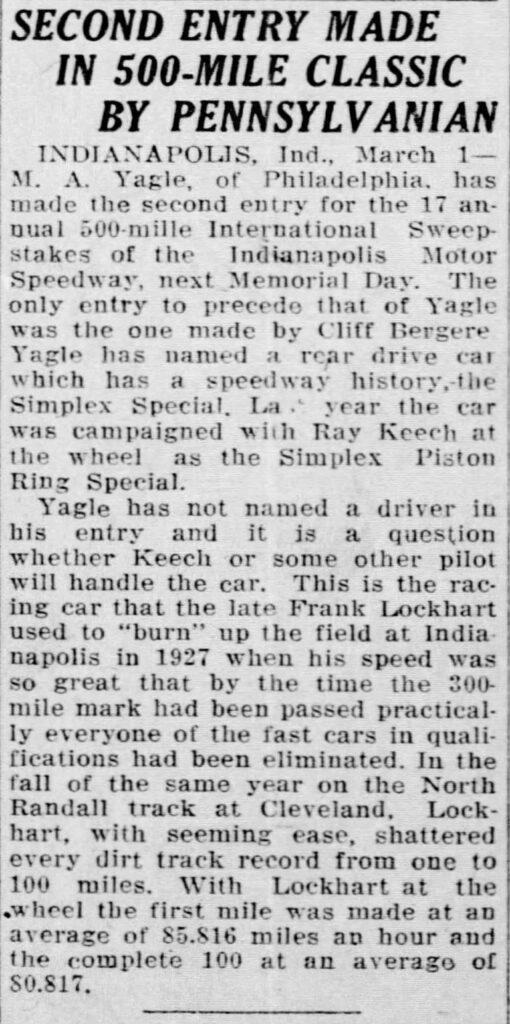

In fact, Maude was so eager for another chance at an Indianapolis 500 win, she was the second entrant for the 1929 Indianapolis 500. Newspapers noted this, however, reporters assumed that M. A. Yagle was a man, using male pronouns in the articles.

Maude’s cover seems to be blown a month before the 1929 Indianapolis 500 after pit lane gossip trickled to a reporter that the owner of Ray Keech’s car was in fact, a woman. Newspapers also reported that she and another woman – Alice Hoffman-Trobeck– requested to be permitted into the garage and pitlane.

“Horrors! Women are trying to break down the last male stronghold in the sports and automobile world!” Ray Priest wrote about the situation.

Maude and Alice’s requests to be permitted into the garage and pitlanes were denied.

Despite this setback, Maude was still an involved owner – involving herself as much as she could. Sitting in the grandstand directly across from her pit box, Maude was constantly clocking her car’s lap times, keeping meticulous records.

Ray Keech qualified sixth, however, he spent most of the race in second place behind the defending Indianapolis 500 champion – Lou Moore. It seemed the second would be the most Ray and Maude would be able to achieve in this race. Fate intervened on Lap 157, however, when Lou Moore’s engine stalled during a pit stop and it took the team seven minutes to get the car running again. Ray inherited the lead and cruised to a victory – cementing them both into Indianapolis 500 history.

The triumph was short-lived though. Sixteen days after Ray Keech’s Indianapolis 500 victory, driving Maude’s car, he was killed in a wreck participating in the Altoona 200.

Ray Keech was just 29.

The car was rebuilt with the intention to race it again, the rebuild costing $4,000 (or approximately $68,000 in 2022 money). Jimmy Gleason – another Philadelphia native on his way to stardom – was tapped to drive Maude’s car.

The rebuild was done by the first of September, and the car was entered into an event at the Bridgeville Board Track, near Pittsburgh. Jimmy won the twenty-five-mile sprint as well as the five-mile sprint. The car was also entered at Woodbury the following weekend with Jimmy topping the speed charts during the time trials, but a broken piston would force them to withdraw that weekend.

On September 21st, while racing at the Mineola Fairgrounds in New York, Jimmy Gleason was involved in a vicious wreck that threw him from his car, onto the track. If it hadn’t been for a rookie police officer, quick to jump over a rail to rescue the racer, it would have been certain death. Nonetheless, he was initially thought to have a fractured skull and jaw, and all of his teeth had been knocked out. Doctors were not sure if he would survive these injuries.

Newspapers reported that Maude had been in attendance and witnessed the accident. Upon learning of the severity of her driver’s injuries, Maude collapsed and she had to be taken to a hospital for what the newspaper described as ‘severe nervous shock’.

The car was quickly repaired though and Dave Evans piloted the car a week later – the car proved to still be fast until a mechanical breakdown forced Evans to retire.

Jimmy Gleason miraculously recovered and returned to the car at the end of October to close out the 1929 racing season. This was the last race Jimmy Gleason raced for Maude Yagle, as the pair parted ways at some point in the offseason.

For the 1930 racing season, Maude hired Frank Farmer – another Philadelphia local to drive her car. Their season included that year’s Indianapolis 500, entered in hopes of replicating the magic of the year before. Farmer qualified a respectable eleventh, however, a crash on the 69th lap gave Maude and Frank a 21st place finish.

The 1930 season did give the pair some success though. On July 4th, Farmer broke the record at Langhorne Speedway – completing a mile around the track in 37.25 seconds. On October 19th, Frank Farmer won his first career race, also at Langhorne.

1931 did not provide any success. Maude’s car failed to qualify for the Indianapolis 500 and Frank Farmer was injured in the car two weeks later. It seems that Maude and Frank parted ways, Zeke Meyer piloting the car for the races that the car was entered in for the rest of the 1931 racing season and Meyer continued to race for Maude into the 1932 season. Newspapers reported that she had entered the car into the Indianapolis 500 with Zeke Meyer however, at some point, he ended up in a Studebaker and it’s unclear what happened to Maude’s car.

Maude reunited with Frank Farmer at some point over the summer and it was Maude’s car that Frank was in when he met his tragic end on August 28, 1932. During a qualifying heat at Woodbridge Speedway, he tangled with Bill Neapolitan, suffering a compound fracture of his skull, a fatal injury.

Frank Farmer was 32.

While the newspapers did not report her reaction to the fatal injury of her driver, as far as I can tell, Maude never entered another race as a car owner.

It doesn’t seem like a far stretch to assume that the deaths of two of her drivers and the near-death accident of another would have an impact on an owner. Relationships are formed between owners and drivers and it isn’t hard to imagine the grief and guilt that Maude might have carried. Maude stepped away from motorsports completely – never mentioned again in newspapers as a car owner or a spectator. And while we can never know if Frank Farmer’s death was the exact reason that spurred her seemingly deliberate departure from the motorsports world, it seems that these two events were related.

Maude Yagle lived a comfortable life with her husband in Philadelphia, until she passed away in 1968, living a full 85 years. Despite this full life, Maude didn’t live long enough to be allowed into the garages and pitlane in Indianapolis.

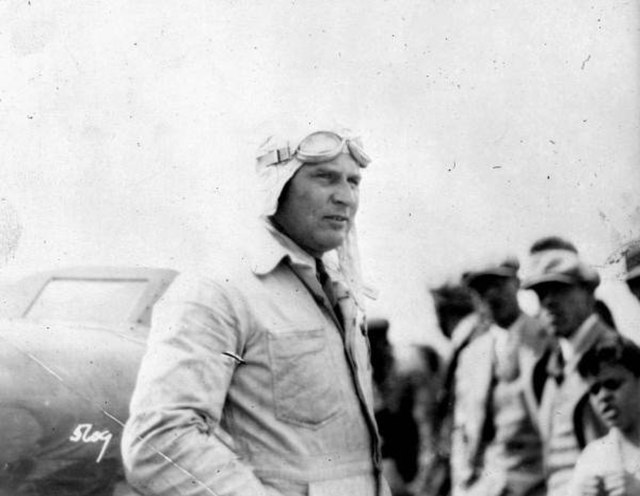

By the time of her death, Maude and her achievements had almost completely faded from the collective memory. Not even her hometown newspaper mentioned her, as they frequently had during her car ownership days. She was largely left forgotten until celebrations began for the 100th running of the Indianapolis 500 when she became mostly a trivia answer, with only a few regurgitated facts, and a picture.

Maude Yagle was a coal miner’s daughter who loved motorsports and didn’t seem to be bothered by the fact that she was dipping her toes into what is still – even 93 years later– largely considered a man’s sport. Maude Yagle made history as the first female car owner to win the Indianapolis 500, despite not being allowed to step into the garage or pit area of Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and deserves to be remembered as wholly as possible, not just as a piece of trivia.

Thanks for telling the story about Maude, I love reading about motorsports history.

Great story. Thank you for telling it.